Eddies—swirling currents that can transport heat and freshwater throughout the upper ocean—are ubiquitus in the worlds oceans, including in polar regions. During the the SODA project, we saw that subduction of eddies can trap heat below the surface and transport it deep under the sea ice (MacKinnon et. al., 2021).

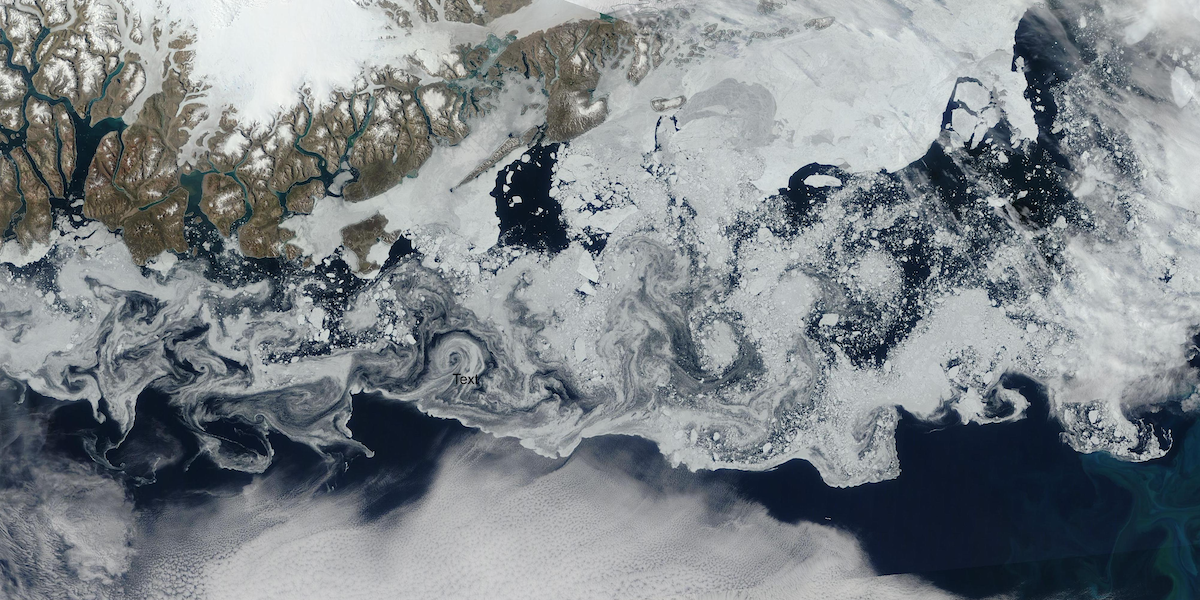

Moreover, filaments and eddies are commonly seen in satellite imagery of sea ice in the marginal ice zone (fig. 1), as they’re revealed by the transport and convergence of sea ice floes. Understanding the structure and evolution of these currents and the role that they play in ice-ocean feedback processes remains an active area of research.

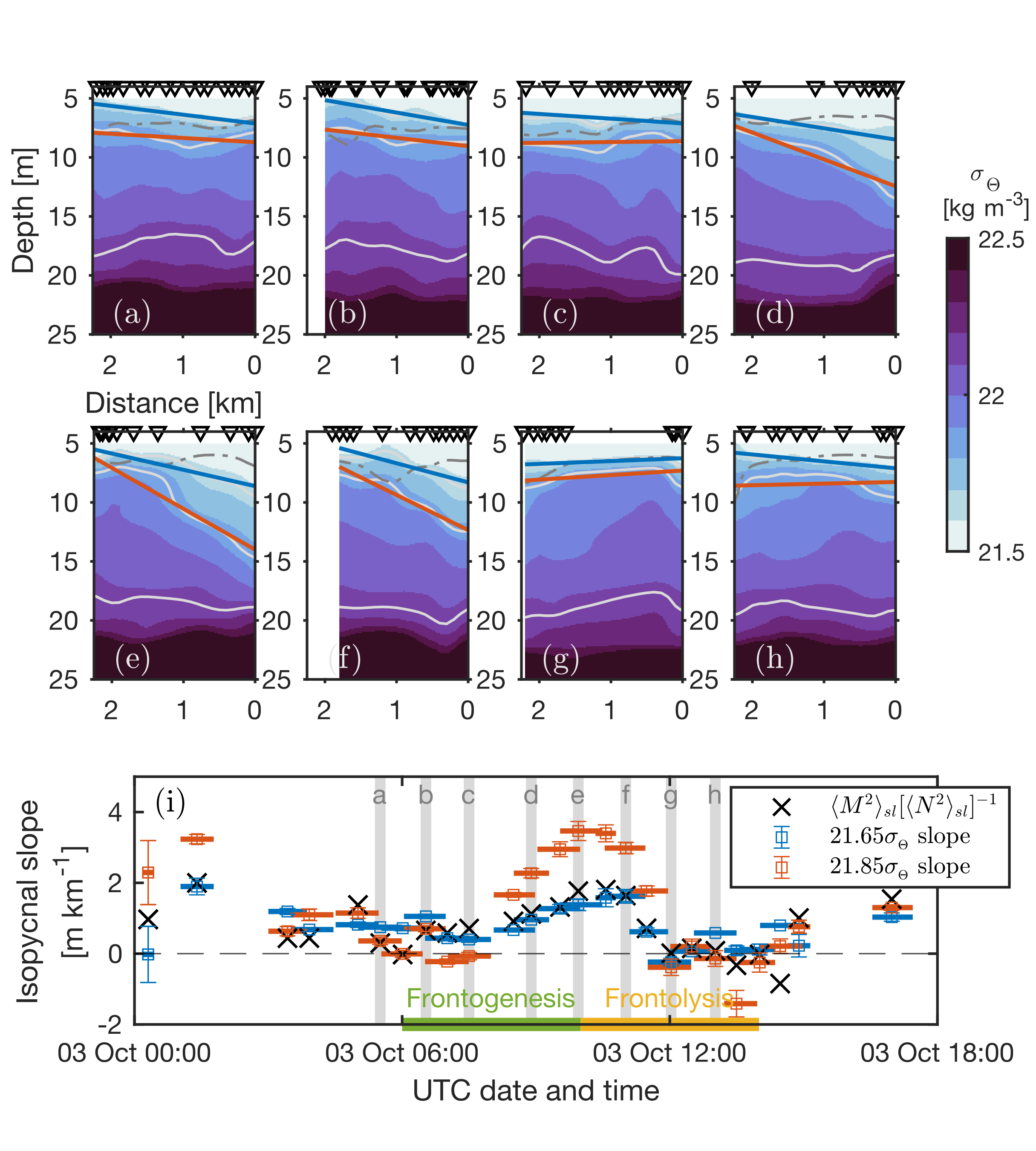

I am particularly interested in how these upper ocean features interact with sea ice. For example, during my PhD, I analyzed high resolution shipboard measurements of upper ocean temperature and salinity in an “ice-following” reference frame along the edge of a submesoscale feature in the marginal ice zone (Brenner et al., 2020). The measurements showed an interesting temporal evolution of the upper ocean structure (fig. 2) that we didn’t expect, with an initial strengthening of the meltwater front, followed by frontal slumping. At the time, we speculated this variability might have been partly related to the influence of sea ice on wind stress modifying frontal dynamics compared to open-ocean settings. However, making measurement sufficient to fully describe these small-scale processes remains challenging in polar regions.

Floe-scale effects further impact the evolution of these eddies and surface currents in the marginal ice zone, impacting rates and scales of energy input through baroclinic conversion and energy loss through ice-ocean friction (Brenner et al., 2023). Part of my ongoing postdoctoral work aims to investigate those effects through high-resolution coupled numerical modelling.

Related publications

-

Brenner, S., Horvat, C., 2024. Scaling simulations of local wind-waves amid sea ice floes. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans., 129, e2024JC021629. doi:10.1029/2024JC021629.

-

MacKinnon, J., et. al, [including Brenner, S.], 2021. A warm jet in a cold ocean. Nat. Comm., 12(1) p.12 doi:10.1038/s41467-021-22505-5.

-

Brenner, S., Rainville, L., Thomson, J. and Lee, C., 2020. The evolution of a shallow front in the Arctic marginal ice zone. Elem. Sci. Anth., 8(1), p.17. doi:10.1525/elementa.413/