In polar oceans, sea ice mediates air-sea exchanges of momentum and energy. While it is easy to think that the sea ice isolates the water column from direct wind forcing, the highly dynamic nature of sea ice makes this a more complex system to understand. This comlexity was the focus of my PhD work, with my dissertation: “The role of sea ice in mediating atmosphere-ice-ocean momentum transfer”.

Using a set of mooring measurements in the Beaufort Sea as part of the SODA project, I have investigated a range of topics related to ice-ocean momentum transfer, including sea ice roughness; inertial oscillation strength; and surface waves in the marginal ice zone.

These questions continue to be a central focus for ongoing research — including how velocity constraints due to floe-scale effects further impact the transfers of momentum and energy across the atmosphere-ice-ocean boundary.

Sea ice roughness

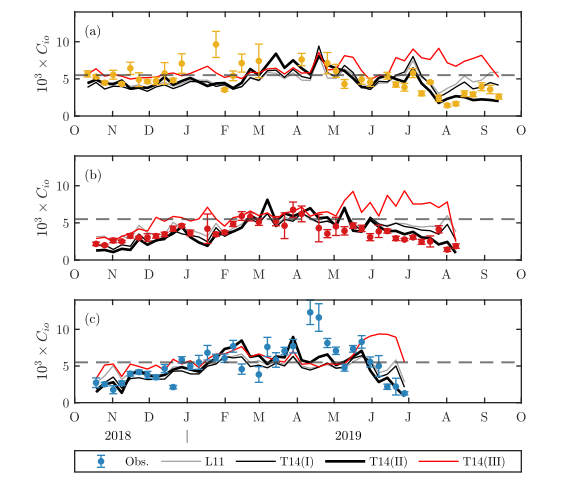

Calculation of surface momentum fluxes across the atmosphere-ice and ice-ocean interfaces typically uses bulk drag laws, that include a turbulent transer coefficient—or “drag coefficient”. The value off this drag coefficient depends on the surface roughness. Sea ice is geometry is characterized by discrete roughness elements (i.e., ice sails and keels). The drag coefficient can be parameterized as a combination of skin drag on the level ice (depending on micro-scale roughness) and form drag on these larger roughness elements.

Making use of data from the SODA mooriongs, I compared in situ values of parameters describing ice-ocean drag with those calculated from an ice geometry-based parameterization scheme (see fig. 1) By analyzing why mismatches occurred, I made recommendations for future iterations of the scheme—which primarily revolved around improving parameterizations of subgrid sea ice geometry, such as floe size distributions (Brenner et al., 2021).

I am interested in extending these results to other study regions and timeframes using extant mooring records.

The increasing seasonality of Arctic sea ice, and shift to a higher proportion of ``smoother’’ first-year ice is leading to a shift to a more “slippery” boundary layer, and more mobile sea ice. Through the use of emerging remote sensing products (such as ice roughness measurements from IceSAT-2) and numerical model outputs, ongoing work is considering the the varying contributions of drag coefficient changes and ice mechanical weaking in observed increased trends of ice velocity.

Inertial oscillations

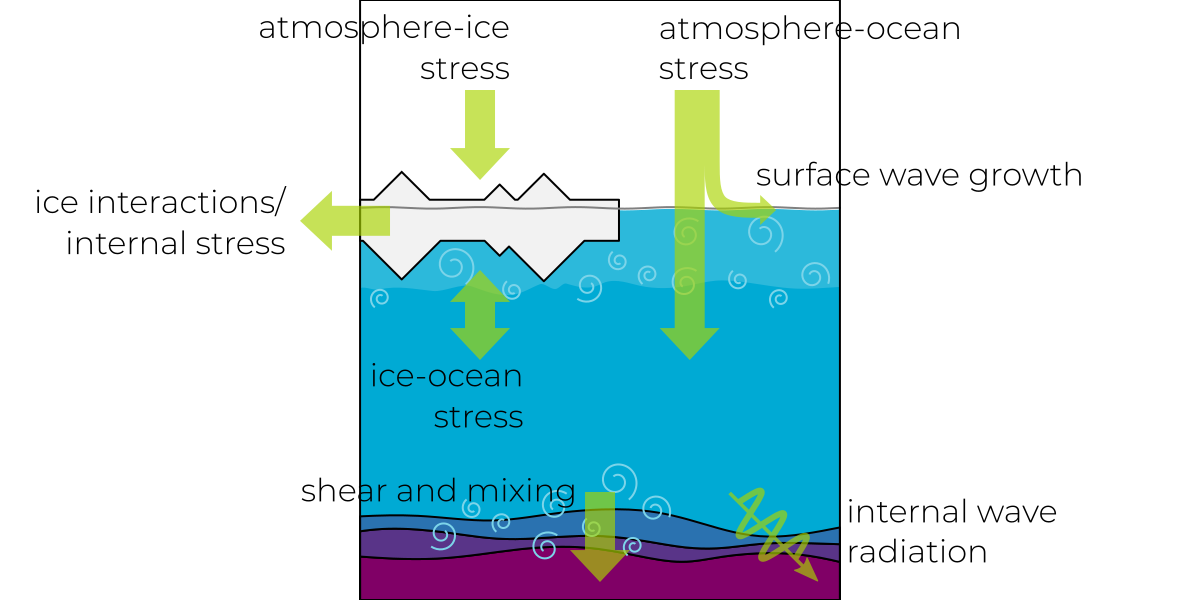

Inertial oscillations are rotational motions of the mixed layer that are a natural resonant response to wind forcing. These oscillations also provide a pathway for energy to be transfered from the atmosphere into the ocean interior, through the generation of near-inertial waves. Seaonal variability in the strength of the inertial response in the Arctic provides evidence for the damping of inertial oscillations by sea ice.

Due to their fairly simple physics, mixed-layer inertial oscillations provide an ideal test case for the potential of sea ice to impede the transfer of momentum and energy from the wind. Using a simplified, one-dimensional, coupled ice-ocean slab model (schematized in fig. 2), some of my PhD work explored these relationships, and noted that mechanical weaking of the sea ice is permitting greater stress transfer to the ocean—even in the midwinter ice pack (Brenner et al., 2023). However, these effects are timescale-dependent: while ice damped high-frequency motion (like inertial oscillations), there is evidence that the low-frequency “Ekman transport” is minimally impacted by the presence of sea ice.

Surface gravity waves

In the open ocean, atmosphere-ocean momentum transfer and upper ocean mixing are mediated by surface gravity waves. Within the marginal ice zone (MIZ), that is disrupted as the ice damps the waves. Wave-ice interactions are a subject of much active research within the community.

With the SODA mooring array we also made measurements of surface waves, which Cooper (2022) compared to Earth-system model results to test existing model parameterizations of wave damping by ice. The wave characteristics measured by the moorings showed a preponderance of small, locally-generated waves existing within leads and gaps between sea ice flows—even up to 100 km within the sea ice edge. These local waves were absent from Emodel results using standard parameterizations, but may be an important part of sea ice and upper-ocean evolution. Using a wave model, SWAN, I was able to show that the surface geometry — dictated by the combination of sea ice concentration and floe size distribution — set constraints on the available open-water fetch available for wind-wave growth, proposing methods for estimate the properties of these locally-generated waves (Brenner & Horvat, 2024).

I continue to be interested in interactions between sea ice and surface gravity waves. In particular, I wonder how the combination of locally generated waves and ice-attenuated swell might impact ice-ocean momentum/energy fluxes in the marginal ice zone, and how to acount for those effects in “flux-averaging” methods of surface stress calculation.

Related publications

-

Brenner, S., Horvat, C., 2024. Scaling simulations of local wind-waves amid sea ice floes. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans., 129, e2024JC021629. doi:10.1029/2024JC021629.

-

Brenner, S., Rainville, L., Thomson, J., Crews, L., and Lee, C., 2023. Wind-driven motions of sea ice and the ocean surface mixed layer in the Western Arctic. J. Phys. Oceanogr., 53(7), 1787–1804. doi:10.1175/JPO-D-22-0112.1.

-

Cooper, V., Roach, L., Thomson, J., Brenner S., Smith, M., Meylan, M., Bitz, C., 2022. Wind waves in sea ice of the western Arctic and a global coupled wave-ice model. Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. A., 380(2235), p. 19. doi:10.1098/rsta.2021.0258.

-

Brenner, S., Rainville, L., Thomson, J. Cole, S. and Lee, C., 2021. Comparing observations and parameterizations of ice-ocean drag through an annual cycle across the Beaufort Sea. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans. doi:10.1029/2020JC016977